The truth is simply this: I have no memories of the Sterling Hall bombing. I’d worked until late that night and I slept soundly. Although I lived only a few blocks away, the sound of the explosion did not awaken me, nor did the subsequent wail of police and emergency vehicle sirens. My most vivid memories of the Sterling Hall bombing were created more than two decades later.

The truth is simply this: I have no memories of the Sterling Hall bombing. I’d worked until late that night and I slept soundly. Although I lived only a few blocks away, the sound of the explosion did not awaken me, nor did the subsequent wail of police and emergency vehicle sirens. My most vivid memories of the Sterling Hall bombing were created more than two decades later.

August 24th, 2010 marks the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Sterling Hall on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus. One man, researcher Robert Fassnacht, was killed in the blast. Four men were accused of carrying out the bombing. Three were tried and found guilty. One has never been apprehended.

But this event affected countless lives in a myriad ways. For some, the aftermath brought swift changes. For others, the consequences were more incremental, more subtle: ripples from a pebble tossed in a stream, “butterfly effects.”

This week, representatives of the UW-Madison Oral History Program and Wisconsin Story Project have set up a StoryBooth in the Memorial Library to collect personal stories and recollections: Take a seat, pull the curtain, and let the camera record your story for posterity.

How vivid will these shared memories be? How accurate? I don’t know the answers to these questions; but I do know that memory is often frangible. Told and retold, a story often takes on a new shape.

I’ve told the story I’m about to share with you only once. Today I realized how it had changed – at least for me – since it first appeared in print.

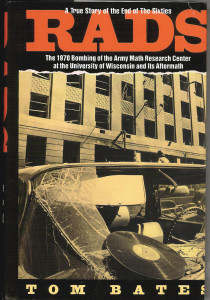

Seventeen years ago, in 1993, I wrote a story for The Badger Herald about Tom Bates, author of RADS (“A True Story of the End of the Sixties”).

I remembered that the story had been published twice and that I had objected to one version because there had been a change to a sentence near the end that I felt altered the tone of the story. This afternoon, I went to the University Archives to look at the bound volumes of The Badger Herald. When I located both versions, my memory was confirmed: One important word had been changed.

But my memory had failed me with regard to another important aspect of the story. When I began to transcribe it, I was shocked by a seeming discrepancy in dates: The story was first published on April 26, 1993, in a special “New Student Issue” mailed students who would be entering the UW-Madison in Fall semester. This issue was not distributed on campus. The story was then published on May 4, 1993 in a regular edition of The Badger Herald. But the story being told takes place on a “dreary November day.”

I remembered struggling with the story, but I had forgotten how long it took for me to cut it loose. Fearful and uncertain, I had written and rewritten the story many times. Editor Andrew Welcyczko coped with my tears and excuses and kept pushing and prodding until I finished the story and turned it in to be published.

It was a bleak story, told in a dull, flat, unemotional tone. It told the story of a man who had tried to reshape his past and failed. At the time, I worried that it was too harsh, perhaps unfair. In retrospect, I think I was fearful that with Bates I was looking in a mirror and seeing my own reflection because I had recently abandoned a chunk of my past and was trying to shape a new future for myself.

Perhaps that is why I objected so vehemently when “unhappy memories” became “regrettable memories” in the first version – and why I insisted it be changed in the second version. Given the gift of hindsight, I think perhaps Andrew’s choice of modifier may have been more appropriate than mine – at least at the time.

I do not know if Bates ever read the story – and if he did, what he thought about it. After living in Wisconsin for several years while he wrote and researched RADS, Bates moved back to Portland, Oregon and spent his remaining years in journalism. He died on December 16, 1999 of pancreatic cancer.

Rereading the story today, I have no regrets about having written it. I do not see anyone but myself when I look in the mirror. Times have changed and so have I. If I think at all about “reshaping the past” it is because I’m tempted to insert some links in a story that was originally written on an IBM Selectric typewriter. And I wonder if Bates was accurate when he attributed that quote to Magritte. I used Google to search for the quote and the results were negative.

The story below is an unaltered version of the original: It may have some unintended typos, but it has no links. As I’ve often reminded newspaper readers over the years, I write the text: Someone else writes the headlines and subheads.

One final reminder: I retain the copyright to the text and it may not be reproduced without my explicit written permission.

“The Hiroshima of the new Left”

RADS author Tom Bates dives deep into an event Madison would rather forget…

An exclusive interview by Nadine Goff

Bates is sitting behind a small table on the second floor of the University Book Store. He’s here to sign copies of RADS, his recently published book about the 1970 bombing of the Army Math Research center on the Madison campus of the University of Wisconsin.

It’s almost 1:30 p.m. on a dreary November day, and right now he has no takers. Book store personnel eagerly report that there were a lot of people who stopped by earlier, during the lunch hour.

Sitting next to Bates is an unprepossessing woman who appears to be in her forties. Her name is Jane. She says she was a friend of Bates’ when he attended graduate school in Madison. She says she’s come to keep him company.

Strolling back and forth in the vicinity of Bates is a security guard. Not a usual feature in the general books department of the UBS.

HarperCollins publicist Ron Longe had expressed concerns about Bates’ safety during a telephone conversation the previous week. Had the interviewer heard about any demonstrations? Would Bates be picketed during his visit to Madison?

No, it seems unlikely, were the replies. After all, the majority of the students currently enrolled in the UW-Madison hadn’t even been born when the bombing occurred. Why should they demonstrate?

As it turned out, there were no demonstrations. There was one minor disruption. Dwight Armstrong, one of the men convicted of the 1970 bombing had come up to the second floor to confront Bates. He was hastily removed from the scene. The security guard apparently earned his keep.

Information about the disruption was not easy to obtain. No was who was present offered it. It had to be laboriously extracted.

Tom Bates seemed to have found this minor disruption unsettling: after all, Dwight had originally cooperated with Bates. He is cited in the RADS acknowledgments as one of the people whose “honesty made this book possible.”

It’s a bit after 1:30 p.m. The book-signing is over. The interview is next.

Jane has been telling Bates about her problems with elderly relatives. The overheard portions of her litany seem to bear witness to an unhappy life. Now, she is anxiously assuring Bates that she is happy with her life. She’s not eager to depart, but when she does, it is with the hope that she and Bates will see each other again before he leaves Madison.

A contemplative walk

Tom Bates rises from his chair and prepares to don his coat for the wintery walk to Sunprint, where the interview will take place. He is very tall. Most people who seem formidable in photographs and on television seem diminutive in the flesh. Not Bates.

Walking up State Street to Sunprint, Bates is wary, tentative. This may not be an easy or even successful interview.

The Madison print media has not been particularly kind to Bates of RADS. Is this the cause of his reticence? Perhaps. Or perhaps it is the natural reticence of a writer-reporter who suddenly finds himself the subject of some other journalist’s scrutiny.

Winter coats doffed. Table selected for unhindered (and “un-overheard”) conversation. Food and beverages atop the table. The interview begins in earnest. Slowly. Gradually becoming more relaxed and productive.

Why did Bates write RADS? Lots of reasons. Some more revealing than others.

“When you’re an editor, you’re always wishing you were on the other side of the desk,” says Bates. He adds that editors often suspect writers and reporters are “having all the fun.”

Bates was an editor at the Los Angeles Times. He left that job to write RADS.

Living in a bitter era

Earlier, in the late 60s and early 70s, Bates was a graduate student in history at the UW-Madison. His 1972 Ph.D. dissertation was on the political thought of Antonio Gramsci, who became, according to the dissertation, “the greatest Marxist of modern Italy.”

Bates became an assistant professor at Ohio University. As the result of his arrest during a campus protest against the mining of Haiphong Harbor, he lost his teaching job.

“That period in my life always seemed like a waste land. I had spent 10 years trying to be a teacher and that was cut short.”

Bates admits to being bitter. “[I] had to retrain myself as a journalist. I went through the 60s and 70s without making any money. Not until the 80s [did] I make any money as a journalist. During this time, Bates also had a wife and children to support.

By the time he decided to write RADS, Bates says he “already had fame and fortune.” He was “a well-known and well-paid editor.” But something may have been missing.

“The idea of [the] book offered the possibility of making something out of that experience.” Bates is talking about the 60s and the 70s, not the 80s. “Waste not, want not,” he adds.

Bates spent the summer of 1987 on a book proposal. In the fall of 1987 he rented a house in Cross Plains, Wis. for a year. He had received an advance for RADS that he thought would be enough to live on and support his family for the two years he thought he needed to spend researching and writing the book.

The book took almost five years. Bates says he was working on RADS until early August 1992, editing and revising.

Re-living the experience

The research for RADS was extensive. According to Bates, he has accumulated ten large cartons of research material. He interviewed approximately 500 people, tape recording about 100 of these interviews.

Bates says he reviewed thousands of pages of documents, including original police and FBI field reports. There were dozens of notebooks with news clippings to review, a lot of which had been organized by the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau.

The UW-Madison Oral History Project was another important source of information, says Bate. The time limits restricting access to many of the interviews were just expiring at the time he was conducting his research. Not all are available, however. Paul Soglin’s interview is restricted until 2039.

Bates says he also spent a lot of his advance on travel and long distance telephone calls as he gathered information and conducted interviews.

Among the many interviews Bates conducted were those with brothers Dwight and Karl Armstrong, two the men convicted for the 1970 bombing, and their sisters, Lorene and Mira. Speaking about the Armstrong family, Bates says, “They always wanted to tell their story – the boys in particular. [I] convinced them I could do a fair and compassionate job.”

Hitting too close to home

Karl Armstrong has been quoted as saying he was “disgusted” by RADS. A high school acquaintance of Karl’s claims Armstrong told him not to read RADS because “it was a piece of shit”

Bates says “[I] think people would come away [from reading RADS] with a more favorable impression of the Armstrong brothers.”

Other people who were active in the Madison anti-Vietnam war movement have also been critical of RADS for a variety of reasons. Among them are Jim Rowen, who was instrumental in exposing the relationship between the theoretical research done at the Army Math Research Center and its “practical” application in the war in Vietnam and David Wagner, a founder the of the underground newspaper Kaleidoscope.

Bates defends RADS: “Many books could be written on this subject and they’re welcome to write them. I couldn’t write their books for them. I could only write my book as I saw it.”

Bates quotes Magritte: “No one every really knows what happens.” He adds, “I think he’s right. There’s always room for doubt.”

“I did the best I could to get to the bottom of things. I’m sure there are areas where I didn’t get to the bottom of things and we maybe never will. There is a lot of grist to chew on for a long time.”

One criticism of RADS has been that it lacks footnotes. Bates responds:

“Almost every line of [the] book is based on primary sources, so I would need another book to write out the footnotes. I thought of it was a journalistic rather than an academic book. Footnotes were never mentioned by my editor.”

How can Bates include dialogue about events he clearly did not witness?

“[I] can reconstruct dialogue because I have thousands of pages of uncensored interviews from [the] weeks following the bombing. And the, in many cases, I could re-interview [people]. Things that seem impossibly detailed are because of this.”

It’s time to conclude the interview. Bates has another appointment. We haven’t gotten around to some of the more specific criticisms of RADS, particularly those that deal with Bates’ interpretations of the causes of some things. Earlier in the interview, Bates has sad he “didn’t do much theorizing,” claiming he “left that to the academicians.

Else where, however, Bate has defended his explanation of how the physical abuse inflicted upon Dwight and Karl by their father may have lead them to become involved in the bombing of the Army Math Research Center. This depiction of a dysfunctional family is one of the aspects of RADS that has apparently been most distasteful to Dwight and Karl.

Closing in on the waste land

We’re waiting outside Sunprint for Bates’ taxicab to arrive. It’s a gloomy afternoon. The interview has been productive, but demanding. Both interviewer and interviewee have been cautious, each, no doubt, for different reasons.

“You’re the only one in town who really interviewed me,” says Bates. He thinks the resulting article will be a good one.

A frisson of fear. A determination to be alert and cautious. Is Bates trying to butter up his interviewer?

No, he’s not. He tone is one of sadness, as he explains that, yes, he has talked to other newspaper reporters, but only after the fact. He says he has only been asked to react to criticism already in print. He really hasn’t been given an opportunity to talk about much else until now.

What will he do now that RADS is finished?

“It doesn’t matter what I do next,” says Bates. He supposes he’ll go back to his home in Oregon and get to know his teenage sons. Bates sounds a bit weary, a bit disappointed.

Perhaps it’s the gloomy weather. Perhaps it’s the less than hospitable treatment he feels he has received in the Madison media. Perhaps it is the exhaustion that often accompanies authors as they criss-cross the nation on promotional tours.

Bates’ notion of a waste land lingers. It is oppressive, contagious and laced with unhappy memories.

Originally published in The Badger Herald on May 4, 1993